Top 10 of ~300 projects in Carnegie Mellon's Intro CS Course

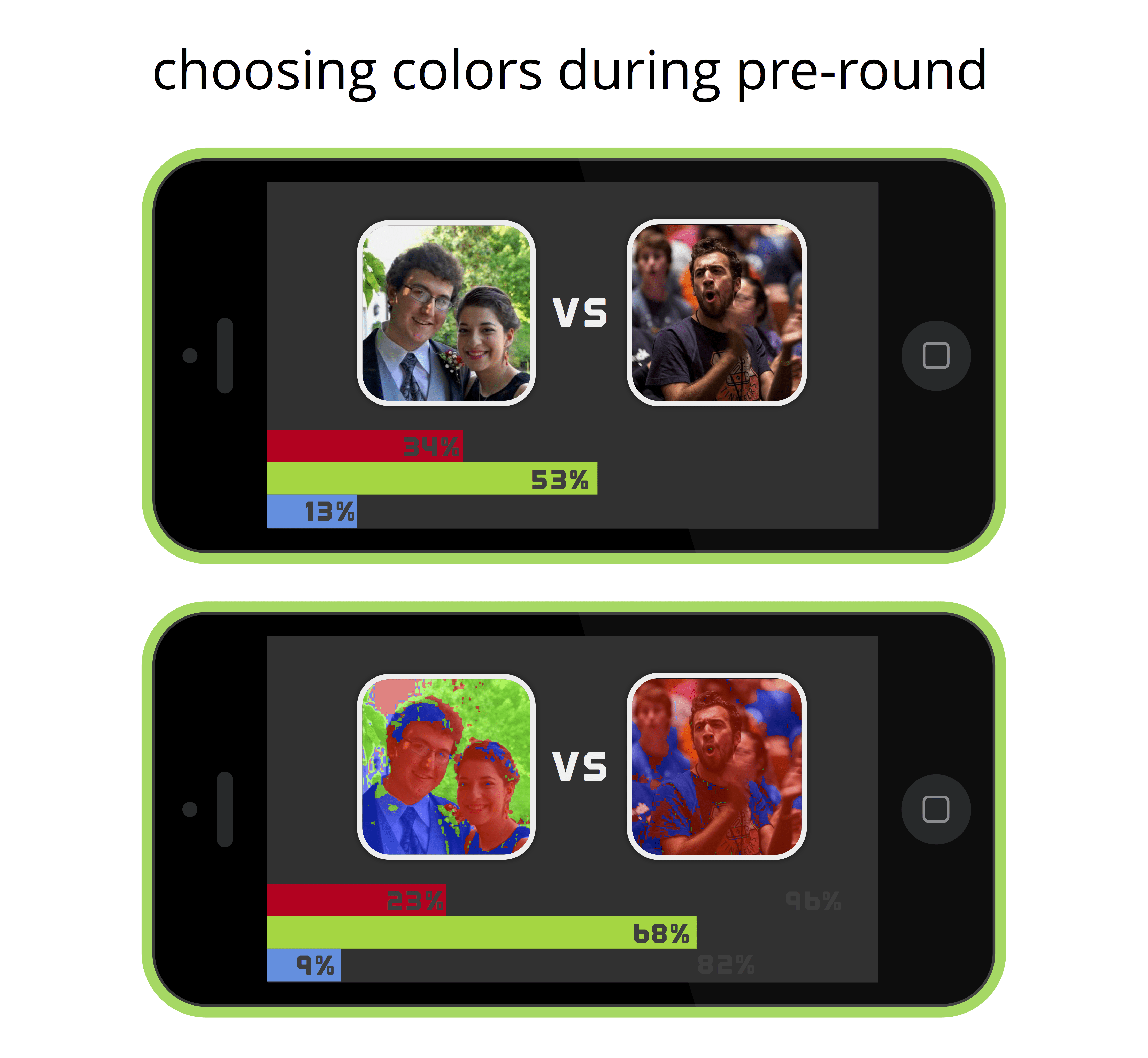

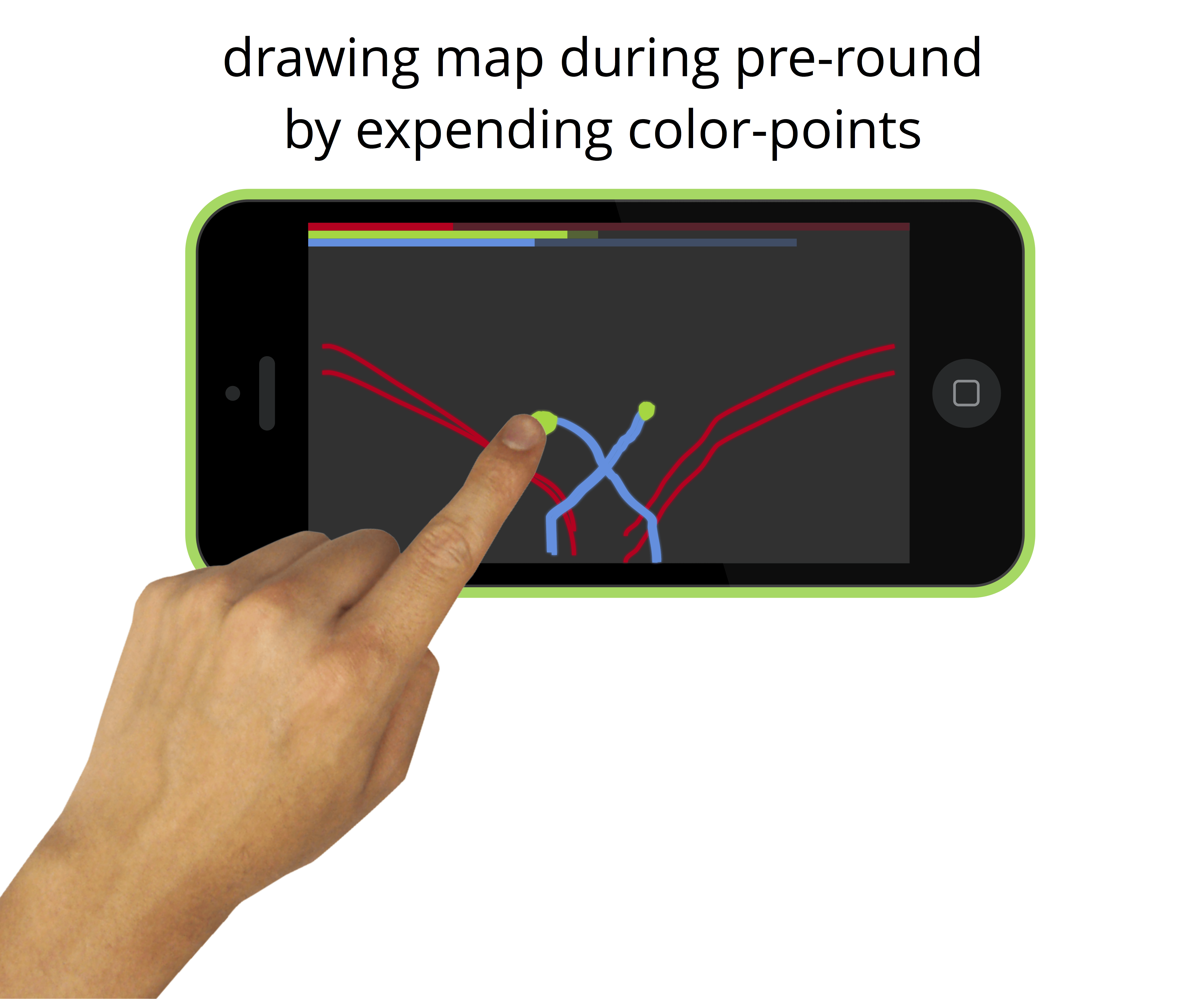

Top 10 of ~300 projects in Carnegie Mellon's Intro CS CoursePRIMARY is a multi-platform, multi-player, Facebook-integrated arcade game. Players sign in with their Facebook accounts and then select among random photos of their opponent to extract the primary colors from those images. These color levels determine the quantity and speed of the construction of that player’s defensive structures (walls) and their offensive projectiles (balls).

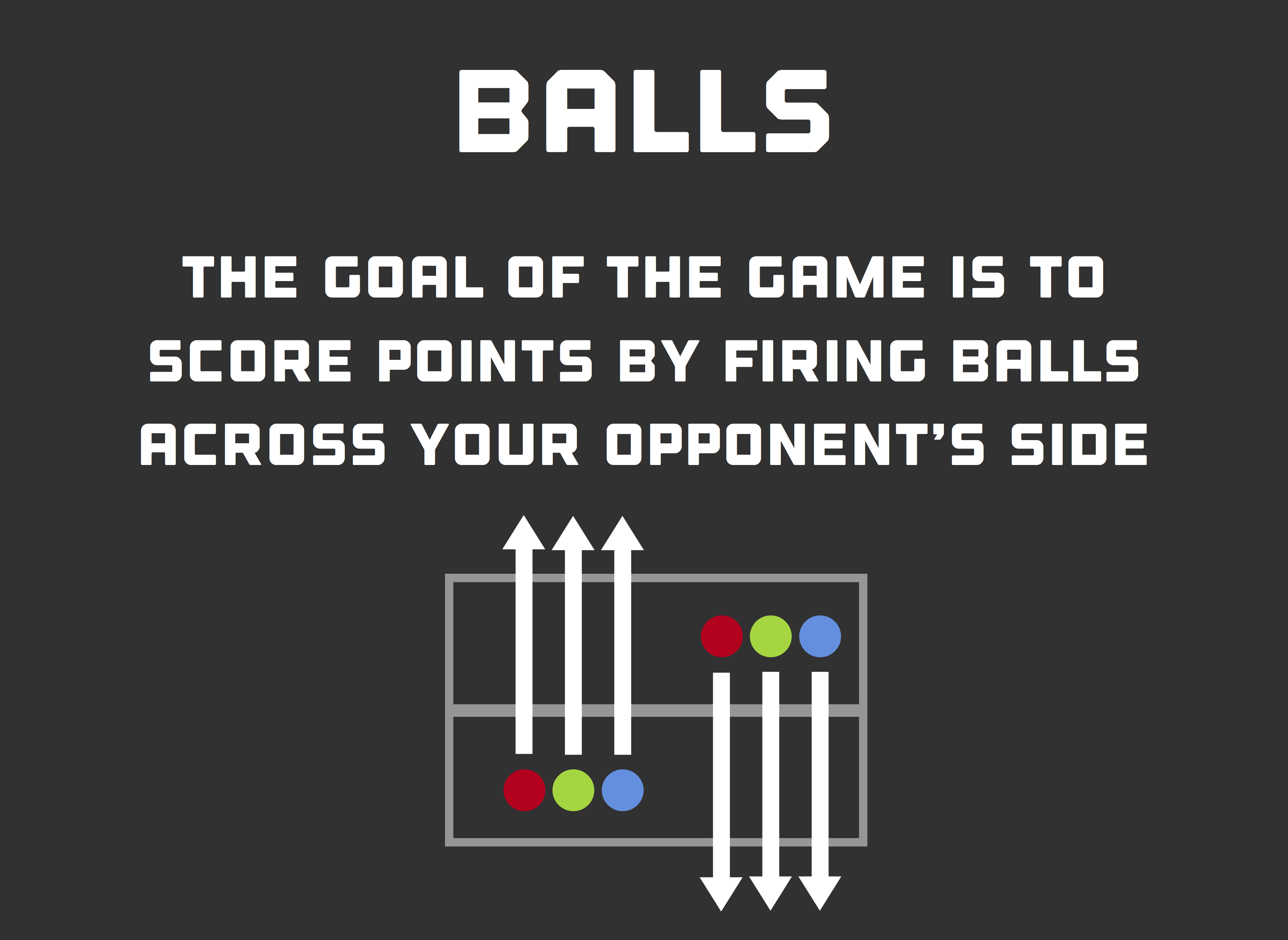

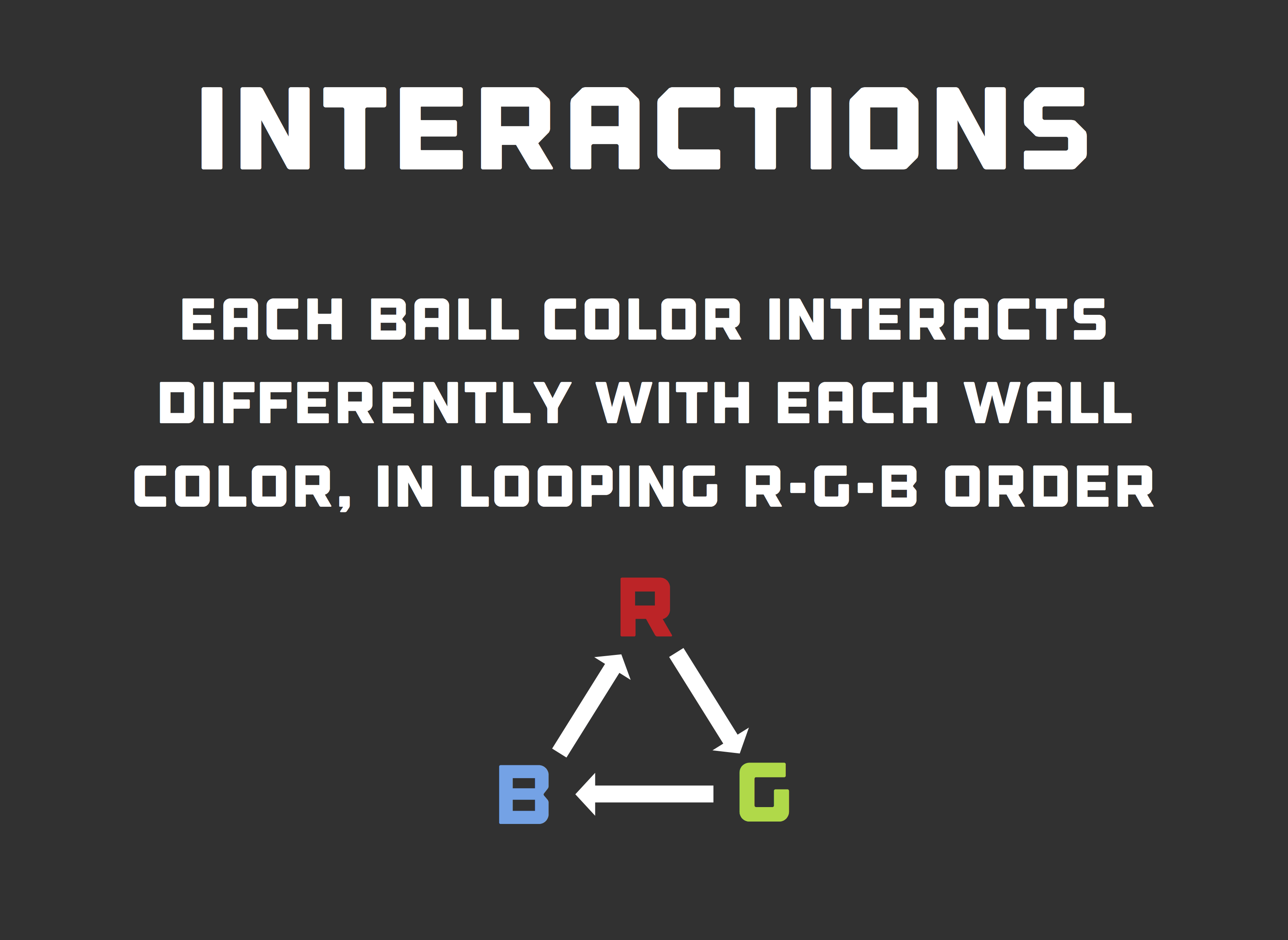

The objective of the game is to score as many points as possible during the 50-second round by flinging balls across the opponents screen. Walls and balls can come in each of the three primary RGB colors (red, green, and blue), and interact with each other based on these colors. For example, balls will pass through walls of the game color, but will by deflected by walls after them in RGB order. All of the specific combinations are enumerated in the included interactive tutorial.

PRIMARY’s architecture is split into two logical sections, each using MVC abstractions: the backend server and the front-end clients.

The back-end server uses Facebook’s excellent Tornado web server, and specifically using its experimental shim for event-loop compatibility with Python 3.4+’s asyncio (PEP 3156, formerly known as “Tulip”). This was chosen for future-proofing reasons, and because it will enable scaling the codebase to interface with coroutine-/future-/task-producing modules. However, as of the final deliverable, PRIMARY’s backend is mostly blocking (w.r.t. network and disk I/O, as well as CPU cycles in the case of the color processing algorithms). Additionally, the back-end server uses Python 3’s enum class to explicitly define and maintain a 7-state state machine, which is the essence of the game engine. This state machine is nicely abstracted using decorators (such as @property and @setter), making the state-changing code relatively declarative, as well as free from explicit synchronization logic at the caller-side — state changes, as with most game data, is communicated via WebSockets to the clients and vice versa.

Pillow, a well-maintained fork of Python’s PIL library, is used to process the images from Facebook. A custom (but minor) fork of the official Facebook Python SDK is used to interface with Facebook’s OAuth2/GraphAPI 2.2. See: github.com/aroman/facebook-sdk. I created this fork myself specifically for this project, as it contains some minor but essential patches to bring compatibility with Python 3.4+ and other newer modules. PyMongo is used to interface with PRIMARY’s database, which is MongoDB. (The database is used for persisting long-expiry Facebook OAuth tokens as well as caches of player profiles and high-score data.)

The front-end clients use Backbone.js and jQuery for DOM-based rendering and interactivity, as well as PhysicsJS and PixiJS, which are used (respectively) to implement the Physics engine and the WebGL-based rendering engine. In the course of developing this project, I found some bugs in the PixiJS library, and I submitted patches to that project’s GitHub repo, which were soon merged into master. See: github.com/wellcaffeinated/PhysicsJS/issues/132#issuecomment-64964805 “Classical” inheritance is used where possible to promote DRY code, and all of the client’s “magic numbers” and other tune-able constants are defined in a single Engine file, which is used by both the arcade board as well as the player pad clients.

There were a number of important architectural challenges to consider and overcome in building PRIMARY. The biggest is perhaps the three-way state synchronization of the game. That was achieved through a combination of an enum-backed state machine in Python, switch statements in JavaScript, and WebSockets and some exploitation of currying (partial invocation) other functional programming strategies.

Another major challenge is the coordination of the players’ multiple “profiles” — the data returned from the Facebook API, their in-game, in-memory state, their in-memory (but immutable) WebSocket handler, and their on-disk MongoDB profile. To unify all of these profiles, I created what I am calling the “Lazy Liaison” pattern. This class, found in liaison.py, lazily-loads content from these various sources as required by the game, encapsulating the sources of these data and exposing them in a simple, light-weight interface. The app server maintains an OrderedDict mapping these liaisons to their web socket handlers, which makes for effective and expressive organization of the game’s critical “moving parts”, by combining stable sort-ordering with constant-time arbitrary access.

One other important architectural decision was in using streaming base64 encodings of the images. Initially, these images were served as static content (written to disk), but this proved poor for UX (the row-by-row loading was undesirable) and maintaining this “image bin” proved unwieldily and overly complex. By simply writing the encoded image stream to an in-memory buffer, rather than to disk, and then piping this through a base64 encoder and finally transforming the bytes into to a UTF-8 string for easy transmission via WebSockets, this problem was elegantly solved.

Finally, another significant area of engineering focus and experimentation was in the development of the “color” algorithms. The code is simple enough to be mostly self-documenting, but I will add here that the reason the pixel-wise, all-or-nothing color mapping strategy was chosen (instead of simply summing the constituent R, G, B values from the colors) was because that in testing this approach, the percentages all tended toward equidistribution — likely because of grays and other colors which move the overall percentages toward stable averages. By explicitly ignoring such “grayish” colors (using some hand-tuned heuristic values), as the algorithm in use today does, this problem is largely solved.